I love answering questions about Jewish Food history, and some time ago, in my newsletter, I asked people to email me with anything they wanted to know. My long-time friend Julie responded with some queries about American Jewish delis. As fate would have it, the most common topic I was asked about while on my recent lecture tour in America, and also following a recent Zoom food talk I delivered also connected with the Jewish aspects of delicatessen food. So I figured this would be a great time to answer these questions, and more, by providing a short history of the American Jewish deli.

But first the questions. Julie asked, first of all, about the seeming contradiction between the famous overstuffed sandwiches, full of “delicious, slow-cooked brisket, corned beef, etc.” with the fact that “the majority of the Jewish immigrants who arrived from Russia, Ukraine, etc. at that time hailed mostly from shtetls and would have made do with much less lavish food and cooking.” How did the poverty food of their past jive with the luscious and abundant portion in the deli that allegedly represented their cuisine?

She also wanted to know why Israel doesn’t have more Jewish delis. (Julie and I worked together in Los Angeles, but both moved to Israel subsequently.)

And finally, the most common question I got asked recently was some variation on, “Is Jewish deli food really Jewish?”

I’m going to leave Julie’s second question for last, and will begin by answering the other two questions together.

The Origins of the Jewish Delicatessen

Jews immigrated to America in waves, and there was a large wave of primarily German Jews who moved to the States in the mid 1800s. There were part of a larger German migration, including non-Jews and Jews alike. Many settled in New York; in truth, you can’t really talk about American deli without talking about New York City. These German immigrants started selling the preserved foods they knew from the old country — sausages, smoked or pickled meats, various salads, pumpernickel bread and preserved fish, etc. The only significant difference between the Jewish and non-Jewish German delis was that gentiles had pork products and Jews used goose meat instead. Not yet sit-down establishments, these stores were really the first American delis (of a sort).(2)Jane Ziegelman, 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement p. 168

These German Jews might not have been well-to-do, but they certainly didn’t match the background or economic status of the next wave of Jews to arrive, the Eastern Europeans. From 1880 to 1920, approximately 2 million Jews from that region moved to the U.S., with the vast majority settling in New York City, largely on the Lower East Side. And as Julie correctly pointed out, the most of them came from impoverished backgrounds. In Hungering for America, historian Hasia Diner points out how in many ways, the abundance of food in America contrasted with the lack thereof in Europe, acting as one of the main driving forces in that Great Migration.

It was this wave of immigrants that truly created the American Jewish delicatessen as we know it. Though they lived in the same areas as the earlier German Jews, they less frequently purchased foods from them, as they were still too poor. Largely they ate at home, buying meat from the local kosher butchers (of which there was quite a preponderance.) Many knew the art of peddling from Europe, and continued selling from pushcarts on the Lower East Side. By the early 20th century, about halfway through the Eastern European migration, NYC officials were cracking down on pushcarts, so many of them turned into permanent stores. These and the butcher shops are what grew into the classic deli.

Around 1910, some of these merchants had room to set up a few tables inside their stores. Also, one of the most popular food fads at the time was the sandwich, an excellent option for newly industrialized workers who needed a lunch on the run. So they also began putting meats between slices of the rye bread they knew from Europe, and guess what?

A sensation was born.

Were the Deli Foods Jewish?

Some of the preserved meats that were made using goose in Europe, were made using beef in America.(4)David Sax, Save the Deli: In Search of Perfect Pastrami, Crusty Rye, and the Heart of Jewish Delicatessen p. 25 But more importantly than that, many of the specific meat products they sold came from different parts of the European Jewish diaspora. Alsatian Jews had been known for the art of charcuterie for centuries. The pickelfleisch they make is likely the ancestor of American corned beef. It might not have been a Jewish invention, but other regions of France do not feature a tradition of beef charcuterie.(5)Joan Nathan, Quiches, Kugels, and Couscous: My Search for Jewish Cooking in France p.215

Hot dogs, meanwhile, were served even in the proto-delis of the German Jews, but marked an American-Jewish alteration on a German-style wurst. And no discussion of Jewish deli can ignore the king of the preserved meats: pastrami. Different than corned beef in preparation (pastrami is brined, then dry spiced, then smoked), and thus in flavor, most scholars trace its roots to Turkey, via Romania. More a preservation technique than a food item, Jews in Romania typically applied the method to poultry, while non-Jews might have used whatever animal was most readily available.(6)Merwin Pastrami p. 20-21 In the U.S., Jewish delis started using inexpensive cuts of beef. (Both the brisket used for corned beef and the plate, or deckle, from which pastrami is made were less expensive, tough cuts, that were softened by the long preparation, final steaming, and not-too-thick-not-too-thin slicing that most delis put them through.(7)Gil Marks, Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, various entries.)

Joining these classics were dishes such as American turkey breast, classic Ashkenazi braised brisket and roast beef, Russian knishes, Polish Jewish chicken soup with matzo balls and more. As food writer David Sax explained, “Suddenly, the foods of a people dispersed for nearly two thousand years came together in one corner of Manhattan. Romanians tasted the dishes of Poles and Litvaks, Russians cooked for Ukrainians and Germans.”

Thus, the deli was not only Jewish in that many of the foods had genuinely Jewish origins, but also in the blend that was served there. The only reason that these dishes which came from different European countries were being served under one roof is that each was beloved by some Jewish community. Thus, the melting pot delicatessen was not just Jewish, but specifically American-Jewish. As Diner put it, “Although east European Jews had not eaten these foods before migration, as American Jews they learned to think of them as traditional.”(8)Diner Hungering p. 201

And it wasn’t only the foods that were diverse. The clientele were equally varied. Scholar Ted Merwin writes that

delicatessens enabled the descendants of Jews from different social classes and different Ashkenazic (eastern European Jewish) nationalities to forge a common American Jewish identity. In the kosher delicatessen, the free-thinker (atheist) and the frum (observant) Jew could literally break bread — typically rye with caraway seeds — together, as could the top-hatted capitalist and the leather-capped socialist.(9)Merwin Pastrami p. 7

So yes, I believe it is 100% fair to say that the American delicatessen as popularly recognized, and the foods classically served in them, are indeed Jewish.

The Deli Grows (as do its Sandwiches)

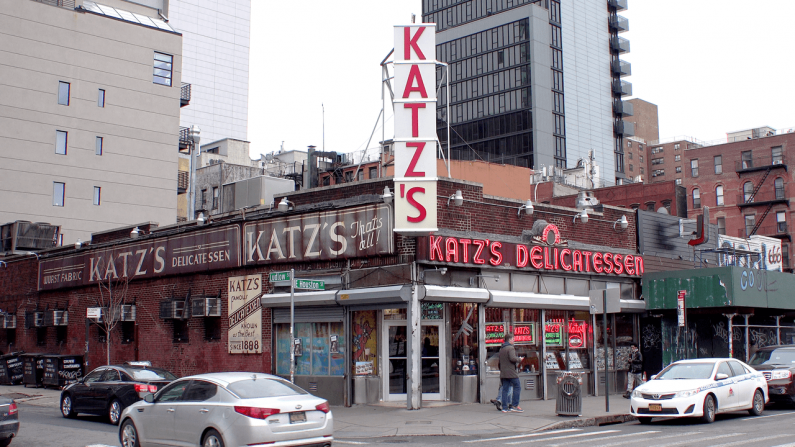

The start of the boom period for American delis was the end of World War I, with the approximate peak Around 1930. This explosion was fueled, in part, by the success of the prior generation of Jewish immigrants. The second generation, their kids, largely left the Lower East Side behind and moved uptown, or to Brooklyn and Queens. Jewish delis followed them to their new homes, without abandoning the old stronghold. Merwin estimates that there were approximately 2,000 delicatessens in New York City in 1931.(10)As quoted in Sax, Save the Deli, p. 27

In addition to this upward mobility, secular Jews were finding success in the entertainment business. It was at this time that we start to see the birth of so-called “kosher style” delicatessens, in addition to the traditionally kosher ones. They might not have served strictly kosher meat, but there were still no pork products, nor mixed milk and meat (at least in the beginning). While still the minority (they were outnumbered approximately 3 to 1 by kosher delis in NYC), these also became some of the best known, particularly those in the theater district near Broadway, associated with the new stars of the entertainment medium.

It was these latter delis that took a page from their entertainer clients and added some showmanship to their offerings. They created “overstuffed” sandwiches, some so large you’d need to be a hippo to be able to take a single bite. These sandwiches also manifested the success of the delicatessens’ clientele; just as daily meat was a sign of increasing Americanization, mile-high sandwiches were clearly not for the impoverished. On a parallel note, the same happened with the bagel around this time. What was once a snack-sized Jewish treat in Poland grew to enormous size in America.

Also reflecting the increasing secularization of American Jewry, many of these delis became less and less kosher, even in “style.” One of the most famous (potentially the most well-known) American deli sandwich is the Reuben (probably named for the uptown Reuben’s delicatessen that claims to have invented it). Featuring (among other ingredients) the forbidden combo of corned beef and swiss cheese, it would never show up even in the earlier kosher style delis, let alone a truly kosher one. Other Broadway-area delis became famous for their cheesecakes. And in time, even bacon found its way into some “Jewish” delicatessens.

Decline of the Deli

If the second generation made the deli a success, the third generation stood by as it slowly died out. Just as their parents moved uptown and to the outer boroughs of New York, they moved out to the suburbs of New Jersey, Connecticut, Westchester and Long Island.

The two best books on the American Jewish deli, Merwin’s Pastrami on Rye and Sax’s Save the Deli (very different books, and both excellent in their own ways) offer up an array of elements that led to the situation where we find ourselves today — relatively few remaining Jewish delis, and even fewer kosher ones. This post is already long, so I will summarize them briefly here:

- Further Upward Mobility – As some Jews found greater wealth in the suburbs, they integrated more into American society and identified less as Jews. They had less desire to consume the foods that were previously associated with the Jewish people. They also found lots of equally good, albeit unkosher food in that new bastion of suburban life, the supermarket.

- Religion – While some Jews became more secular and thus could eat at any number of restaurant types, others became more stringent in their observance of kashrut, and didn’t even accept the kosher status of the remaining kosher delis.

- The Holocaust – With the destruction wrought by the Nazis in Europe, there was no new wave of immigrants that followed and needed to find their own footing in America.

- Operating Costs – Particularly in cities, rents became astronomical. Insurance costs also skyrocketed. Even those delis that were able to purchase their property still faced fairly narrow profit margins on sandwiches, and customers resisted price hikes that would make the restaurants financially viable. This held true even more for strictly kosher delis, that had to pay higher prices for their raw product, and more for kosher supervision.

- Changing Tastes – Increasing cosmopolitanism led to a wider array of restaurant offerings. Even kosher customers took increasingly to Italian, French, Chinese and Sushi restaurants, choosing them over the simple-but-homey delicatessen fare. Furthermore, starting in the 1970s, a wave of health consciousness led to a backlash against the fatty, salty foods that were the backbone of the American Jewish deli.

Summarizing the demise of the deli, Merwin wrote, “The delicatessen was a victim of its own success. By flattering Jews’ social and economic aspirations, it helped to propel them into the middle class.” And Sax takes this idea further with, “In less than a century and a half, the Jewish delicatessen came to New York, multiplied like crazy, and died off even faster. In fifty years’ time, it is possible that no delis will exist at all in New York City.”

Thankfully, there has been a slight resurgence in the past few years, with some hipsters looking back to “roots foods.” Schmaltz and gefilte fish are finding greater popularity and even artisanal expressions. How long this will last, and how far it will go remain to be seen. Perhaps the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic will bring rental prices in cities down, and enterprising deli-owners will find ways to ensure a greater amount of long-term success. Who knows?

On a final point, though, I must move away from America and answer Julie’s other question about Israel. Her question about why there are not more delis in Israel echoes the same questions I often hear from people about finding it hard to get a real bagel here, or even a traditional chicken-and-matzo-ball soup.

To answer this, we need to remember a very important point that I often make in my lecture about Israeli food. In America, about 90-95% of the Jews are of Ashkenazic heritage. Ashkenazi Jews make up around 65-75% of worldwide Jewry. But in Israel, only about 45% trace their roots to Ashkenazi cultures. We Ashkenazi Jews must remember that unlike in most of the rest of the world, we are a minority here in Israel! So yes, with some searching, you can find some of the classic Ashkenazi staples. But the foods of all of the Sephardic and Mizrachi Jews, and of those who are neither Ashkenazi, Sephardi or Mizrachi (such as Ethiopians, Georgians and many Italians and Greeks) will be represented more widely here.

I hope you found this interesting, but more than that, I hope it inspires you to be in touch. Please send me any questions you may have about Jewish Food. What is the origin of X? Why do Jews eat Y? When did Z become popular for Jews? etc.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Ted Merwin, Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli p. 17-19 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jane Ziegelman, 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement p. 168 |

| ↑3 | Hasia Diner, Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, & Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration p. 180 |

| ↑4 | David Sax, Save the Deli: In Search of Perfect Pastrami, Crusty Rye, and the Heart of Jewish Delicatessen p. 25 |

| ↑5 | Joan Nathan, Quiches, Kugels, and Couscous: My Search for Jewish Cooking in France p.215 |

| ↑6 | Merwin Pastrami p. 20-21 |

| ↑7 | Gil Marks, Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, various entries. |

| ↑8 | Diner Hungering p. 201 |

| ↑9 | Merwin Pastrami p. 7 |

| ↑10 | As quoted in Sax, Save the Deli, p. 27 |

Cooking Jewish Culture: Choucroute Garnie à la Juive

[…] to begin with! I would definitely be more careful in selecting my meat next time (many recommend a pastrami, which is both smoked and pickled). I think that ensuring they are really buried in the sauerkraut and cooking liquid might help as […]

Q&A: Why Can't I Find a Good Bagel in Israel?

[…] posts, I realized that a few of the points I want to make, I already wrote about in my post about the history of the American Jewish deli. But I do have one or two new points I want to add here. So I will summarize and clarify the points […]

Le plus gros sandwich de New York: Une histoire des délices démesurés chez Sarge's Delicatessen et Diner - Nouvelles Du Monde

[…] avons commencé à voir des sandwichs trop farcis, selon Joel Haber, écrivant dans le Goût de la culture juive, lorsque les enfants d’immigrés pauvres, connaissant eux-mêmes une réussite financière, […]