I often hear people asking for new Passover foods, bored with the same stuff all the time. And while I clearly respect tradition, for this holiday especially I feel there is at least an argument to be made for not exclusively cooking what your mother and grandmother did. (Years ago, I even wrote an article — with recipes — just on this subject, suggesting new Passover foods as a way of expressing the freedom we celebrate with this holiday.)

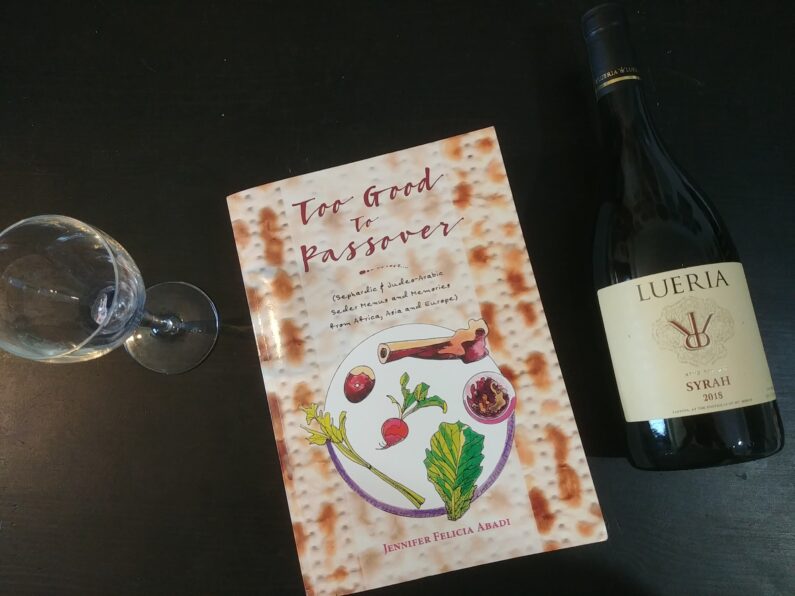

Therefore, this current edition “From the Jewish Food Bookshelf” focuses specifically on a book that can help. It has been out for a couple of years now, but you may not have come across it yet: Too Good to Passover by Jennifer Felicia Abadi. Abadi studies an teaches about the foods of Sephardi and Mizrachi/Judeo-Arabic Jews (or what I even more broadly refer to as non-Ashkenazic Jews — we are a much more diverse people than simply Ashkenazi, Sephardi and Mizrachi). This book goes in depth with the Passover Seder, weekday and post-holiday foods of many such communities from Africa, Asia and Europe. There are bound to be a host of new Passover foods for you to try among the over 200 recipes in this book.

Plenty For Ashkenazim, Too

Inaccurately translated as “legumes,” kitniyot are actually a number of different foods (including beans, rice, corn and various other things) that by custom, Ashkenazi Jews avoid eating during Passover. Without getting in to too much detail, they largely became forbidden due in part to similarities between them and actual chametz — leavened grain which is forbidden on Passover. Non-Ashkenazi Jews, however, largely do not follow this custom, though some communities avoid specific types of kitniyot, while others avoid others or none. This custom has gained a level of controversy in contemporary times especially, now that there is a significant mixing of the cultures in Israel, in particular, and the custom is seen as divisive, hurting Jewish unity. I will not address that point here, nor the logic of the custom itself, as that is out of the scope of this post. But I wanted to at least clarify why many readers might look at this book and write it off as irrelevant to their Passover menus without even examining the book itself.

Now, why is that not the case with Too Good to Passover? Certainly, some of the recipes contain kitniyot. But just because Sephardim and Mizrachim more or less do consume such foods, that doesn’t mean it is all they eat! In fact, kitniyot find their way only into a minority of the book’s dishes, meaning the rest are all good even for those Ashkenazim who avoid such ingredients!

I randomly selected 6 of the 18 chapters in the book (each is dedicated to a separate country, or in a few cases a cluster of a few similar countries). I took two each from Africa, Asia and Europe. Here is a breakdown of how many of the recipes actually had kitniyot in them:

- Egypt: 1 of 10 recipes

- Morocco: 1 of 11 recipes

- India: 3 of 10 recipes

- Turkey: 0 of 8 recipes

- Greece: 2 of 12 recipes

- Spain/Portugal/Gibraltar: 2 of 10 recipes

To be clear, the book also includes foods for the post-Passover meal, which usually contains actual chametz, so I was only looking above at the dishes for the seder and Passover week. I also only looked at foods where the kitniyot was a core ingredient of the dish, not ones where it was an optional serving addition (such as a soup that might be served with rice). Finally, I’d argue that in many cases, the “forbidden” ingredient for Ashkenazim could be left out or altered. For example, a rice dish might be made using quinoa instead, which does not fall into the category of kitniyot, according to most opinions.

Bottom line, don’t avoid this book, simply because you fear it will be worthless to you, if you are an Ashkenazi Jew who doesn’t eat kitniyot on Pesach.

Diverse but Unified Passover Foods

On a somewhat smaller scale, we see that point via Abadi’s book. Moving through this voluminous work (it is nearly 700 pages), we encounter community after community, delving into the foods they eat for one holiday alone. Through that, we discover a number of through lines that tie foods of one such community to others, similarities between Jews in widely spread regions that on the surface might bear little connections to each other.

One example, of course, is the charoset eaten in each community. Of course, I previously wrote about a book that looked only at this topic, but seeing it as one element of the seder meal in each place, it works as a microcosm of Jewish unity-in-diversity. Similarly, the many matzoh-meat pies that crop up in different places show these connections.

At the same time, each country has certain dishes that are unique or at least fairly specific to their cuisine alone. Examples include Tunisia’s Fadd (Calf liver stew with tomato and spices), Iranian Abugushti Gundhi (chicken soup with chickpea flour/beef dumplings), or Bulgarian Torta ot Tseluvki (meringue “kisses” cake with strawberries and cream).

This diversity, and even the different versions of more common foods offer lots of options for you to add new foods to your Passover menu.

The Best Way to Use This Book

As I mentioned, this is a hefty book. Abadi includes over 200 recipes from 23 different Jewish communities. So while someone like me enjoys reading it cover to cover, many people may opt more for a skimming and flipping through approach. Use the indexes to find recipes that look interesting and/or dig down into one specific community’s Passover foods.

Then, at your leisure, you can also read much of the supplementary materials. Abadi includes interviews she conducted with people from each of these communities, the people from whom she culled the many recipes of the book. They add color and personality. I also appreciated that at the intro to each chapter, she includes a brief overview of the cuisine, including common ingredients and flavors.

There really is enough in this book to provide you with ideas of new Passover foods for years to come. Jump through them, try the ones that speak to you, and embrace the spirit of freedom and Jewish unity via the foods you prepare for your seder, or the Passover week!