One of the saddest chapters in Jewish history is also one of the more interesting on a gastronomic level. Following the forced conversions in 15th century Spain, and the Inquisition and subsequent Expulsion, many so-called New Christians secretly maintained Jewish beliefs. Practicing in secret to avoid arrest and torturous execution, they are now known as Crypto-Jews. (1)The better-known term Marrano is a derogatory term that had been used by Crypto-Jews’ enemies, offensively referencing swine. Use of the term is frowned upon these days.

Since food habits are daily, and thus the hardest and least likely to change, foods that were considered “Jewish” could mean a death sentence when Crypto-Jews ate certain telltale dishes. Inquisition court documents repeatedly make this connection clear. In addition to famous tales of such Crypto-Jews conspicuously eating pork to “prove” their Christian faith, many others devised tricks to avoid such transgressions while not giving away their secret. But certainly not every dish consumed related to the danger of revealing their secret lives — most food was neutral when it came to this issue. So what did Crypto-Jews eat? And how did that food develop over the past 500 years?

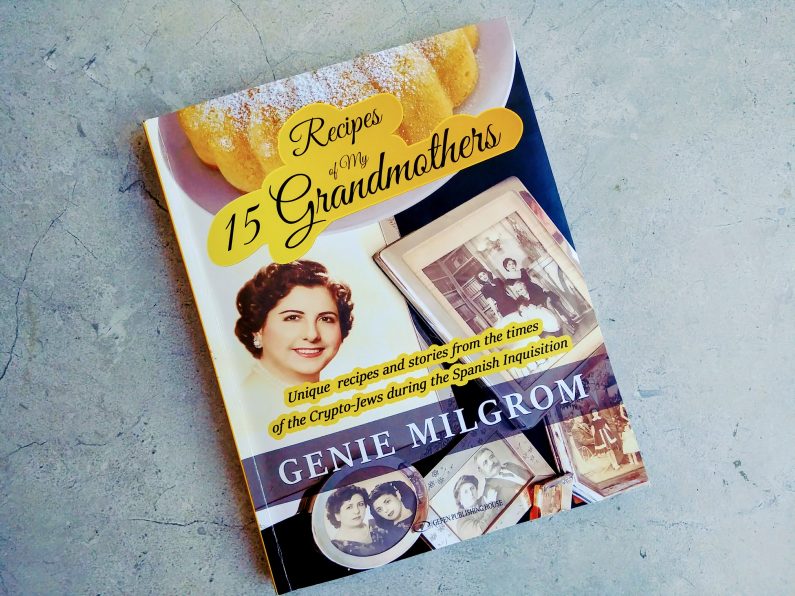

Recently I had the pleasure of reading Recipes of my 15 Grandmothers, by Genie Milgrom.(2)Recipes of my 15 Grandmothers: Unique Recipes and Stories from the Times of the Crypto-Jews During the Spanish Inquisition, Genie Milgrom. I received the book for free from Genie and Gefen Publishing House, here in Jerusalem, after explaining its significance to my research. The cookbook itself is a fascinating personal window onto answering the above questions. And in a series of follow-up emails, she’s been extremely helpful and forthcoming, answering all of my questions with joy.(3)It is due to the friendly rapport we have developed in this interchange that I feel comfortable referring to her in this piece by her first name.

The Book’s Background

In time, she began intense genealogical research, eventually uncovering “an unbroken maternal lineage going back twenty-two generations to 1405 pre-Inquisition Spain and Portugal.” As it turns out (she discovered), she had actually been Jewish all along!

Still, while names and cold biographical facts drawn from archival records may be significant, Genie really yearned to learn more personal details. Turning to her mother, she asked for anything that had been handed down from previous generations. Her mom denied having anything. And then fate stepped in.

Finally, the sad day came when my mom could no longer live in her home, and it was at that moment that I found many old books full of pages of handwritten recipes and scraps of paper with small writing and tiny notes written in light pencil. All of these pages were done in different handwritings, some with more flourishes than others, but always written by the women. With this, I found the recipes of the grandmothers.

While Genie had written and spoken a lot about her genealogy and her research, this discovery led her to edit and compile the recipes into this cookbook. Though an experienced home cook, Genie is clearly neither a professional chef nor cookbook writer. She recruited a cadre of friends and colleagues to help her test cook the recipes, and she reveals in numerous places in the book that she has not even tasted all of the recipes in the book herself. So on a culinary level, this might not hold up alongside other contemporary cookbook favorites.

That being said, there will certainly be recipes in here that will interest and appeal to many readers — recipes that, in fact, will be unique and delicious. More than that, however, the book is a great exploration of a somewhat blank spot in Jewish Food History.

I know of one other book that looks at the subject. Husband and wife professors David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson published the fascinating (and award-winning) A Drizzle of Honey(4)A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spain’s Secret Jews, David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson, culling food facts from Inquisition archives and reconstructing the original dishes. But their recipes, enlightening as they may be, were largely their own approximations and guesses. Genie’s book works as a perfect companion — personal recipe records to pair with the broader archival research.

Unique Crypto-Jewish Food Traditions

Genie writes that she was surprised to find no recipes in the entire collection that mixed milk and meat. When I asked about pork (a major ingredient in Spanish cuisine) she told me, “As a matter of fact, my family recipes only started having pork in Cuba in the 1930s and 1940s.”

Thus, one of the most surprising recipes she uncovered among the collection of handbound books and paper scraps was one for Chuletas — pork chops. She barely could bring herself to read the recipe, but when she finally did, she was the most amused. Though they are called pork chops, the recipe is actually a sort of French toast that is disguised to resemble pork chops! (Yo no hablo español, but according to Google translate, these “mock” pork chops should be called simulacros de chuletas!)

Genie claims that they are “the best look-alike to a pork chop that I have ever seen,” and speculates this dish was designed to throw off suspicious neighbors. I have not made these, nor do I know what pork chops should really look like, but I must admit I find it hard to believe anyone could be truly convinced by anything more than a passing glance at these. Smell and consistency would be dead giveaways. Still, whether or not this was actually their origin, there is undoubtedly an intriguing history cooked into these simulacros. (See recipe at end of post.)

Perhaps the most oft-repeated aspect of Crypto-Jewish life is the persistence of Jewish practices that generations performed, not even necessarily knowing why. Famous examples include lighting candles in a hidden place on Friday night, circumcision and sweeping towards the center of the room (rather than out the door, so suspicious neighbors won’t know they are preparing for Shabbat).

Genie explains that her grandmother only taught these recipes and techniques to her, though she had four other grandchildren. This makes one wonder how much her grandmother knew about her Crypto-Jewish background. Reading through the grandmothers’ recipes, did she too piece together the truth of their Jewish background, or was something more subconscious at play? Unfortunately, we will never know.

Other Jewish Aspects of Crypto-Jewish Cuisine

On a broader level, there are many other crossovers between the recipes in this book and Jewish Food in general. It is worth noting that, as Genie points out, the recipes here are distinct from Sephardic cuisine, as that community blended its Spanish roots with the influences of the areas in which they lived — the Turkey, Italy, the Balkans and the Levant, largely. Primarily, the food is typical Spanish, with adjustments, and developments through time.

Many dishes were things that Genie sees as more or less clearly connected with Jewish holidays. Cocido Madrileño is a clear stand-in for a Shabbat hamin (and the most relevant for my book, so I will leave discussion of it until then). Other recipes appear perfect for Rosh Hashanah (Dark Fruit Cake) and Purim (Orejuelas y Peastiños). She also points to how many dishes there are that surprisingly contain no wheat flour, making them appropriate for Passover.

Finally, though distinct from Sephardic cooking, as mentioned above, there are a number of dishes represented that are indeed Sephardic classics. She highlights her grandmothers’ “Decorated Rice” (saffron rice with raisins, almonds and cinnamon) and the pareve flan-like Tocino del Ciello as Sephardi classics. Bollas and Rosquillas are other common Sephardic pastries that appear in these pages, too.

In short, Recipes of my 15 Grandmothers offers a group of personal and lesser-known recipes for the home cook. But beyond that, it also offers lots of raw material for those interested in digging deeper into the culture of the many generations of Crypto-Jews.

* * *

Chuletas – Tia Paulita

From Recipes of my 15 Grandmothers: Unique Recipes and Stories From the Times of the Crypto-Jews During the Spanish Inquisition

(Tia Paulita was Genie’s great-aunt who first wrote this recipe down.)

2 loaves of thick, country-grain bread (not sourdough, as the flavor overwhelms this recipe)

2 cups milk

1/4 cup sugar

4 eggs, lightly beaten

1/4 cup flour, approximately

Olive oil for frying

Tomato jelly

Several strips of sweet pimento

Reserve some crust from the bread. Mix the milk and sugar and wet the 2 loaves in this mixture until you can form a thick paste with your hands. Add the eggs and mix well. Add a little flour until the mixture is workable with and moldable in your hands.

Mold the mixture into the shape of a pork chop and fry in olive oil until golden brown, turning once on each side.

Cut the reserved crust into small sticks and fry until golden brown. Pierce the fritter with the crust sticks to look like a pork chop bone. Place in a casserole dish and cover with tomato jelly. Decorate with strips of sweet pimento.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The better-known term Marrano is a derogatory term that had been used by Crypto-Jews’ enemies, offensively referencing swine. Use of the term is frowned upon these days. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Recipes of my 15 Grandmothers: Unique Recipes and Stories from the Times of the Crypto-Jews During the Spanish Inquisition, Genie Milgrom. I received the book for free from Genie and Gefen Publishing House, here in Jerusalem, after explaining its significance to my research. |

| ↑3 | It is due to the friendly rapport we have developed in this interchange that I feel comfortable referring to her in this piece by her first name. |

| ↑4 | A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spain’s Secret Jews, David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson |

Karen

I loved this article I am going to follow it up by learning more

Roz

I am wowed by this story .. and grateful that after all the years she was able to find out her back story and all these amazing recipes … another great story of survival..

Jewish Food Bookshelf: Sephardi - Taste of Jewish Culture

[…] roots. Similarly, by looking both at the foods of the Jews while they were in Spain, and at the gastronomy of crypto-Jews, she presents a more complete portrait of the overall […]

From the Jewish Food Bookshelf: A Drizzle of Honey - Taste of Jewish Culture

[…] fasting on Yom Kippur, eating meat during Lent, or avoiding shellfish could betray a Crypto-Jew. And eating foods that were identified as Jewish Foods could prove equally […]