The Jewish Food Bookshelf is wide and diverse. I have previously covered cookbooks, reference works, books that explored the food of a single cuisine, others that looked deeply at individual foodstuffs, and works of history both broad and on a specific topic. (And those links don’t even hit all of them.) But the book I’m covering in this post is not like any of the others. It is a work of food history, but it explores a single, little-known event in detail, and puts it into a broader context as well.

Scott D. Seligman’s The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902 is a rare work of history, in that it digs deeply into a specific topic, furthering the research that had already been done, while remaining an eminently readable book. I read the entire thing in about a day or two, and enjoyed it thoroughly. And even better, the event that Seligman focuses on is generally not known, despite its significance to American, Jewish, and American-Jewish history.

What Was the Kosher Meat War?

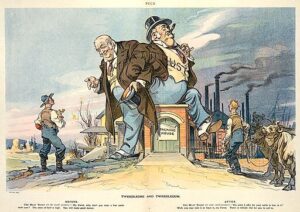

In 1902, on Manhattan’s heavily Jewish Lower East Side, the price of kosher meat skyrocketed, going up 50-100% practically overnight. Accustomed to regularly consuming meat, and generally unwilling to forego kosher meat for the still-expensive, but cheaper, treif meat, Jewish consumers spontaneously banded together to protest. What started as a simple boycott, quickly spiralled into riots, with butcher shop windows being smashed, meat being destroyed before it could be sold, and physcial altercations between locals, butchers, and police.

Notable in the events of Spring and Summer 1902 was that the protest was started and led by women, many of whom were just a few years off the boat in America. This was the first real consumer-oriented protest in America, and became a model for many more in the future. One of the initial solutions that didn’t seem to last, but made its return when needed in future years, was the establishment of consumer-owned co-ops. The movement even gained followers in other neighborhoods of New York, and then even in other cities. Furthermore, while meat prices did, of course, continue to rise, in the short term the protests achieved their goals; most local butchers ended up selling meat at significantly lower prices than their initial raised prices (though still somewhat higher than they had been before). And though it took time, and serious government efforts, slowly but surely the Midwestern meat trust was eventually disbanded via government regulation and lawsuits.

Some Interesting Details

As a spontaneous, grassroots movement, changes were inevitable. In time, egos came to the fore, even though there was no premeditated organization. Power struggles about who would lead and some decisions on how to proceed altered the “face” of the movement. Seligman explores (as best as possible, with little available direct source material) these individual personalities. While the tensions between the individual leaders was sad, and the type of thing with which we may be familiar from any number of other movements, perhaps the most just outcome came about in the end: while the protest primarily achieved its initial goals, all of the leaders were largely forgotten by history. Even when similar protests developed in the years that followed, those who led this protest were not at the forefront then, and were not even invoked by name.

One of the particularly interesting points that Seligman highlights is how in time, men took over the organization, making decisions and leading negotiations. While in itself that may not be so surprising (I can practically hear many of you reading this saying, “Of course they did!), what was more intriguing is he found absolutely no evidence of ill well from the side of the women. Not only did they step back and let the men lead, they even welcomed it. The men who were involved had more connecitons and more experience, and the women were primarily the drivers of the emotionally-laden protest. This is no comment on abilities or the propriety of this shift. Rather, it is very telling about the historical milieu in which this event took place, and the relative statuses and roles that each sex played in life on the Lower East Side.

One aspect that I wish Seligman had explored, or at least mentioned in passing, is the speed at which people’s expectations changed. Most of the protestors were new immigrants to America. When they lived in Europe, most were poor and had very little meat to consume at all. In America, however, beef grew into a daily food item, and the immigrants became accustomed to this habit. (For more on this, see Hasia Diner’s excellent Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, & Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration.) What I find incredible, though still justified, is how in such a short span of time, lifestyles could change so drastically that the feeling towards meat was almost one of entitlement. Clearly, this was partially about justice, and the rapid spike in prices was the result of injustice. So that also plays into the protest movement. But the rapid acculturation, to me, is also one of the main unexplored aspects of this event.

Finally, some of the ancillary elements (and the later changes that came about) underscore the significance of this “war” in American and Jewish history. Seligman highlights the follow-up protests over the coming decades, both focused on meat prices and on apartment rental prices. A recurring theme of antisemitism within certain segments of the population, including police and some other locals, along with ineffectual leaders who promise to care for this population segment and then failed to do so, both have echoes even today. And the government actions against the meat trust itself, paired with their attempts to work around the regulations, portray an interesting example in the development of law and governmental interventions in general.

I recommend reading The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902 if you are interested in a quick read that explores the character of Jewish New York in the early 20th century. The historical resonance of the event that Seligman explores only adds to the book’s value!

No Need to Cause a Riot! Just Pass This Post Along to Others…

Karen Haubenstock

Do you carry both of these books or do I need to order from Amazon, for example? Or might they be available in a library in Israel?