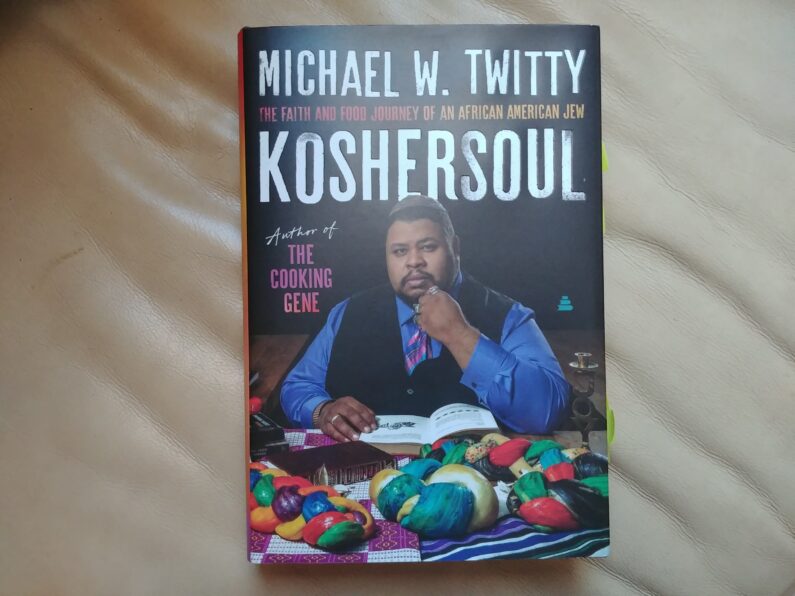

Michael Twitty’s is an interesting combination of personal identities. As he frequently reminds us in his new book Koshersoul, he is African American, Jewish, gay, and a southerner. These all combine to create the passionate blend that is his character, and as a food historian and active gastronome, they also filter into his food. This is a big part of Koshersoul, which focuses most of its attention on the Jewish side of his character (as opposed to his first book, the award-winning The Cooking Gene, which emphasized his Southern, African American roots more). In this sense, Twitty’s new work is a genuinely unique book, and an enjoyable and interesting addition to the Jewish Food Bookshelf.

While the book is unique, that was not a word I chose to describe Twitty himself, opting instead for other adjectives that do not literally mean “one of a kind.” In addition to the food writing, one of Twitty’s other clear goals in this book is to normalize what should by now already be seen as normal: Black Jews. Anyone who has their eyes open knows that there are massive numbers of Jews of color, and yet, most of them can list numerous occasions in which they experienced discrimination, ignorance, or worse from within the Jewish community itself, ashamedly. By peppering his work with interviews with many of his friends and acquaintances who, like him, are Black Jews, while still focusing a lot of attention on their culinary expressions, Twitty stays on his core topic while broadening it into an almost activist text. Rather than speaking of relations between Blacks and Jews, we need to broaden the terms to Blacks and White Jews, or White Jews and Black Jews, or Jews and non-Jewish Blacks, etc.

What’s in Koshersoul?

“Koshersoul” is the term Twitty uses to describe the fusion that takes place in his kitchen and at his table. As he writes in his introduction, “Koshersoul is an eclectic recipe file of diverse and complex peoplehood. My goal is to go beyond the strict borders of what Black Jews eat or how Black Jews cook, or even how ‘mainstream’ Jews (with ‘mainstream’ being nothing more than a polite term for white) have absorbed Black food traditions not usually seen as ‘Jewish.’ It is the border-crossing story of hos the ups and downs of daily existence as a Jew of color affect us from kop to kishkes [head to guts] as we sit down to partake in the soulwarming solace of our meals.”

To that end, Koshersoul blends memoir anecdotes from Twitty’s life experiences, chapters that explore various aspects of the culinary history and meaning of fusions, discussions with many other Black Jews focusing largely on their food lives, a sizable recipe section, and occasional digressions that less directly address food and more connect to the other purpose of his book. In more than one place, Twitty clearly states that this is not a “standard” book, this broad mix thus removing the book from any neat “genre” categorization.

In my view, the book does suffer from this, to a degree. While the reader does get the point and message of Twitty’s book, feeling them as if s/he is soaking in a bath, the more off-topic aspects and tangents tend to distract and weaken the impact the book might have had with a more focused structure.

By contrast, one of the more successful aspects of the book are the various interview segments. They serve to display the vast diversity of Jews of color, and their food choices as well. Thinking that all Black Jews eat the same food would be about as absurd as thinking that all white Jews do! Their different geographic origins, familial histories (born Jewish, conversions of various types, born of one Jewish and one non-Jewish parent, etc.), and personal tastes all contribute to different approaches to their personal gastronomies. Twitty still manages, however, to find the commonalities that create an aspect of “Koshersoul” for all of them.

Future Food History?

To my view, as someone who explores Jewish Food History, Twitty’s work fills an interesting niche. On the one hand, some could argue that this has no place in the study of that subject. Much of what Twitty does and has done previously are artificially created attempts at creating traditions, rather than a document of traditions that exist. I’d respond that the through lines that Twitty traces indicate that while some of the specific dishes may be somewhat individualistic and actively invented, the overall phenomenon of a Jewish subcommunity trying to find meaning in foods that express their identity is one that clearly exists. In other words, an individual dish might be less “traditional,” but the motivations that have given rise to that dish’s creation are widespread and shared by many.

I see Koshersoul as a snapshot of a moment in which some aspects are already better established and others are in the process of solidifying. They may not all persist; some may be forgotten in time, but others are sure to gain traction. And frankly, many Jewish food traditions have been actively created, altered, or renewed throughout our history. So I see Twitty’s work as a document of potential future history at best, and contemporary sociology at least.

When I preodered this book, I was under the impression that it was going to be a cookbook (though I knew that The Cooking Gene was not one). I even listed it in my newsletter among upcoming Jewish cookbooks for the summer. I was surprised by what I got, but still read it excitedly. Still, at least Koshersoul includes a section of about 65 recipes. I have not yet cooked them, but have read them all. Alas, this section has a few weaknesses. A well-written recipe is a hard thing to accomplish (and no, I do not think I have yet developed that skill myself), and this is an area in which Koshersoul coul dhave benefitted from the help of someone more skilled in this specific task. There is a lack of consistent terminology between the recipes, some unclear instructions, etc. Still, a number of the recipes are interesting and sound tasty, so in that sense the recipe section works. It also underscores the diversity of Koshersoul expressions that Twitty forefronts throughout the book.

If you’ve read this far, and are interested in learning more, I’ll just mentiont that the Jewish Book Council is hosting an online event connected with the book in a couple of weeks. My friend Adeena Sussman (author of Sababa) will interview Twitty via Zoom, on September 15. Sign up — it’s free!

Go on… Share this with someone else… (Thanks!)

Jewish Cuisine in Hungary - From the Jewish Food Bookshelf

[…] foods representing the specific conditions of that group. Therefore, a huge part of the Jewish Food Bookshelf is comprised of books that look at the unique gastronomy of Jews in a specific region, such as […]

Food Wins at the National Jewish Book Awards 2022 - Taste of Jewish Culture

[…] W. Twitty’s book Koshersoul received top honors, being recognized with the award of Jewish Book of the Year! This is quite a […]

Does Kosher Soul Food Worth My Time? – Threadminds.com

[…] of the main drawbacks of kosher soul food is that it can be more difficult and expensive to prepare than traditional soul […]