If you’ve attended Hebrew School, or one of many Jewish Summer Camps, you probably know the Hebrew word for Spring: Aviv. It’s an ancient word, that appears multiple times in the Jewish Bible. The only problem is… it doesn’t mean Spring. Or at least it didn’t in Biblical times. Back then, it described a food product, one that is still eaten today. And that, here in Israel, is more or less prepared the same way as it has been for thousands of years!

I’m referring to freekeh (hence the terrible pun in the post’s title), one of my favorite grain products. In brief, freekeh (also called ferik) is not a unique grain, such as wheat, barley or oats. It is a version of wheat, in the same way that bulgur is. Durum wheat (a harder, older variety) is harvested young, while it is still green and moist. Then it is burnt, grains still inside of the hulls, toasting the young wheat.

The resulting product is tasty and nutritious, but was most likely invented as a way of preserving the grain and ensuring against a total crop failure. By harvesting a portion of your wheat early, and preserving it, you can be certain that even if something happens to your harvest (a locust attack, for example), a portion of your food supply will be safe. A later, but very similar invention, is greenkern (grünkern in German) — the same process applied to a different ancient wheat variety, spelt.

In my book, I discuss a Shabbat stew variety made by German Jews that uses grünkern — but that’s a story that will have to wait. For now, I want to focus on freekeh, and in particular its connection to the season we are in right now.

Aviv and the Jewish Ritual Calendar

Furthermore, the root appears in other Semitic languages as well, always referring to a plant (never a season). For example, the capital city of Ethiopia is called Addis Ababa. The name means “new flower” in Amharic, one of the Semitic languages of that country (with Ababa and Aviv sharing a root).

The reason aviv couldn’t have referred to Spring is that in ancient times in this region, there was no Spring! What I mean is that the annual cycle in this part of the world breaks down not into four seasons, but only two — winter and summer. The Tanakh also makes this clear in multiple places, and in reality it remains true today. We only began thinking about four seasons in this area following the influence of European culture. Even then, we named those four seasons at first after the Hebrew months that started them, making Spring (for example) “the Period of Nissan.” Only in medieval Spain did Jews first start to apply the Hebrew word aviv to the full Spring season! And thence to modern Hebrew.

Why did they choose that word specifically to be applied to this season? Part of that stems from the previous major holiday we celebrated, Passover. When that holiday is described in Exodus 34:18, the phrase used is “in the month of aviv.” So if that was the month of aviv, then this would be the season of it! To properly understand the meaning of that phrase, however, you need to understand agriculture in this region.

The two main grains here in Biblical times were barley and wheat. Barley ripened first, and then wheat, and both after the rainy season — in Israel, we only get rain in the winter, virtually never in the summer. Right now, we are in the period between the barley and wheat harvests. In the Book of Ruth, which we read on the upcoming Shavuot holiday, Boaz feeds the titular heroine some kali, i.e. roasted grain.(1)Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, “wheat,” Gil Marks This is the same word used to describe roasting the Passover grain offering, mentioned in Leviticus.

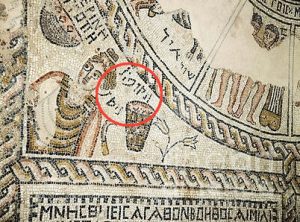

In fact, the specific grain-based sacrifices that Jews made in the Temple in honor of Passover and Shavuot directly relate this food product to the season. On the second day of Passover, the omer sacrifice consisted of unripe barley. Just like freekeh, except with barley instead of wheat, it was cut while still immature and burnt while still in its husk. It was then threshed and ground into fine flour. This was mixed with oil and brought as a sacrifice on the altar. On Shavuot, seven weeks later, the wheat was ready to be harvested, and it was ground into flour and baked into two loaves of leavened bread. They were sacrificed on the latter holiday.

Thus, the period when freekeh could be made from immature wheat should be right around now; the wheat wouldn’t be ready yet at Passover, and would have fully ripened by Shavuot. And in fact, the time for it just ended this past week!

Freekeh Today, the Ancient Way

My friend and colleague Paul Nirens runs Galileat, offering food tours and workshops in the north of Israel. This past Friday, he led a group into the fields not far from the village of Deir Hanna in the Sakhnin valley of the Galilee to watch freekeh being made. (Freekeh Friday?) Unfortunately, I was not able to join him in person, but he gave me permission to share his pictures and video that you see below.

The local Arabs in that area, and around Jenin (and I believe near Hebron) in the West Bank, are among the last who still make freekeh in the traditional way. The only really modernized part of the process is the final stage, when the grains of freekeh are removed from the husk. Traditionally, the burnt hulls would simply be rubbed off (with the name freekeh being based on the Arabic word for “rub”). Nowadays, that stage is done by machine, attached directly to the power take-off (PTO) of a tractor. Other than that, the process remains the same. Here are the stages, in pictures:

Here you can see the green, unripe wheat, waiting to be cut and made into freekeh. Paul really enjoyed this next picture, in which you can see a religious Jewish woman, learning from a hired Palestinian farm worker the method for properly cutting/harvesting the grain.

After the grain has been harvested, it is spread out on nets in the fields. There it dries for a short while, and the nets are also there to cover the grain overnight, if they don’t finish roasting it all that day. This helps protect it from being eaten by birds or other animals. This picture shows the raw and roasted grains, side-by-side.

Next, we get to the most important phase: burning the grain stalks. In this short video, you can see the grain loaded onto a perforated plate, sitting on top of a fire. The workers constantly rake the grain back and forth so it chars without burning up entirely.

Paul told me that one of the cool things about this farm is how they really use everything. The kindling for the fire below is actually the leftover stalks from sesame plants that they also grow. Once they remove the sesame seeds, they keep bundles of the stalks and burn them to roast the wheat for freekeh!

Finally, once the freekeh has been roasted, it remains spread out to cool off and await the PTO-assisted hulling machine!

Final Freekeh Facts

You might be wondering, “what prevents the grain itself from burning when the hulls catch fire?” Since the wheat is so young, it maintains a fairly high moisture content. That, in combination with the short time on top of the flames, plus the constant raking and the protection of the husk itself keeps the grains themselves from burning.

The process, however, also adds another benefit — taste! While in some ways freekeh tastes rather similar to bulgur (especially when made in its cracked variety, rather than its whole grain style), it also features an underlying, mildly smoky flavor.

Another benefit to harvesting the wheat young and roasting it into freekeh is that it ends up being more nutritious than the mature grain. Nutrients that would be used up in helping the plant grow larger remain in their existing state. So freekeh has more protein and calcium, and slightly lower carbs than mature durum wheat. It also has a good amount more dietary fiber. For these reasons, some consider it a “supergrain,” even though that word is pure nonsense and created solely for marketing purposes!

And tying it back to the biblical references I mentioned above, there is actually a similar but different product called frik (or alternatively mirmiz).(2)The Oxford Companion to Food, Alan Davidson, entry on “freekeh” by Anissa Helou Used largely in North Africa, it harvests barley while still young, just like the omer sacrifice of Passover. For that food, they actually parboil or steam it before drying, so it is a different process. But still interesting to see the continuity that exists through time and place with such a useful, tasty and healthy grain product!

Elli Sacks

Brilliant. Thanks!!!

(from a freekeh fan)

FunJoel

Awesome! Thanks so much for reading, Elli!

Mary A MacVean

Hello

I’m trying to find out, for an adult coversion to Judaism class, if barley might have been used as a cover crop. Do you know anything about that?

Thanks so much.