To me, studying food is not an end in itself. It is a way to learn about the people who make and eat it. Which of course is the angle that I am taking in my book. Obviously, I describe the foods themselves, their origins and history, and other interesting things about them. But beyond that, I use them as a way of exploring the Jewish people.

As I mentioned, I’ve begun to drill down on the topic of Shabbat stews (Chulent, Hamin, Dafina, etc.), and part of that intensive research has been talking to people about their family’s versions. I intend to have a full chapter of recipes at the end of the book, so getting them from various individuals is an important element of the process. (At the end of this post, I will also talk about what I am seeking, so feel free to jump to that if you’re not interested in reading the whole thing.) After gathering the first few, I’ve found some of the little details I’ve come across rather interesting.

Turkey to Panama, via Jaffa

For example, one friend sent me her husband’s grandmother’s recipe for Jamin (spelled that way, in the Spanish manner, since her husband’s family came from Panama). The grandmother was born in Turkey, then moved to Jaffa, Palestine, and eventually moved with her husband to Panama. One aspect of her recipe that caught my eye was rice tied up in a cheesecloth and placed inside the pot to cook with the rest of the stew.

The idea of separating the elements in a Moroccan stew grows out of the medieval Spanish version, called Adafina. That stew was cooked in layers, and then served separately as multiple courses in the meal. When the Jews were expelled from Spain, many went to North Africa, with Morocco receiving a large number due to its proximity. Other Jews, however, fled to the Ottoman Empire (as I discussed in my post on Bourekas). And while many Sephardic Jews in that region no longer held onto the tradition of serving the elements separately, in this case it appears to have been preserved. I see in the grandmother’s recipe vestiges of its Spanish origins.

Moroccan Dafina

And speaking of Moroccans, one of the other family recipes I received was for a Moroccan Dafina. The Moroccan Jewish community is one of the more diverse ones, mixing Sephardim with other Jews whose families never moved to Spain in the first place, and with further divisions among that latter group as well. Perhaps as an outgrowth of that, there are three common names for Moroccan Shabbat stews: Dafina, Skhina and Hamin. There are also slight variations on these names, with some for example calling it Adafina (clearly the origin of the name Dafina).

I don’t know if originally there were distinctions between Moroccan Dafina and Skhina, but from what I’ve seen in the many recipes I’ve looked at, today the differences seem to be in name alone. The recipes are rather similar, whichever name is used. I’m currently trying to look more closely at the names to see if they break down at all in line with regions of Morocco or ethnic subgroups, though I haven’t done enough research on that yet.

When I discussed the dafina recipe with the friend who sent it, we discussed the name. I explained to him the Spanish origins of the dish. He mentioned he’d never thought about that connection, but it pleased him and made sense, since his family surname indicated their prior history in Spain. But after explaining the connection of the name to adafina, he laughed saying he’d heard that the word dafina came from the Hebrew word dofen (“wall”), as that was the best spot in the communal oven to put it for overnight cooking! In reality, the word adafina has undisputed Arabic-language origins, meaning “buried” or “covered,” hinting at the original heating method. The pot would be buried in coals to stay warm and cook overnight. He recognized the unlikelihood of the origin he was told, referring to it (when he told me) as “an urban legend.”

Beefy Gibraltarian Adafina

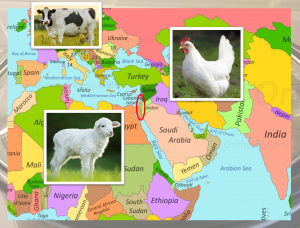

One of the main things that I see when I look at the Shabbat stews from around the world is that two of the main ingredients — the meat and the grain — break down fairly strongly by region. Generally speaking (though by far not exclusively), chicken is the primary meat in Central Asia, lamb in North Africa and beef in Europe. In the book (and in the lectures I give on the subject) I go into more details on why this distribution came about the way it did.

I therefore was surprised when my friend’s description of his family’s Adafina used beef rather than lamb. In fact, he told me he’d never seen anyone put lamb in their stew in Gibraltar. Thinking about this, the most plausible explanation I came up with for starters was that it may be a more modern change. Beef has become a dominant protein in diets worldwide, primarily starting in the mid-19th to early 20th century. With the industrial revolution, cattle were less necessary as pack and work animals, and became a more plentiful and less expensive source of food.

One of the main findings of the survey I made about shabbat stews was this prevalence of beef as an ingredient today. Nearly 80% of respondents, regardless of their country of origin, used beef as their meat. I suggested to my friend that perhaps his grandmother or great-grandmother would have used lamb in her Adafina, and his mother’s use of beef may have been an outgrowth of beef’s modern dominance. He agreed that was a distinct possibility.

The Taste of Jewish Culture

The point of all this is to highlight how much we can learn from food. It is the reason I gave this blog the name that I did. There is obviously much more to learn from Shabbat stews, and that’s what you’ll eventually read (I hope) in my book!

That being said, I also am asking for your help now. I’ve gotten a lot of information on contemporary Shabbat stews around the world. And while they did come from a wide array of areas, some communities were very widely represented. (I don’t really need more Eastern European Chulent recipes, for example.) At the same time, there remain a number of Jewish communities I have not yet reached. So, if you (or someone you know) has origins in one of the following Jewish communities, I would love to receive a recipe and/or description of your/their Shabbat stew. Please send them via direct email, or via the contact page.

In particular, I am looking to hear from Jews in or from: Central Asia (e.g. Afghanistan, Georgia, Kurdistan, Iraq, Persia/Iran), East Asia (Thailand, Singapore, China/Hong Kong, India — all the different communities), Middle East (Syria, Lebanon, Yemen), Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey), Northern Europe (Holland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark), Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Ethiopia) and all over Latin America.

Thanks in advance!